Paolo Sorrentino’s much-awaited The Hand of God (È stata la mano di Dio) became available worldwide on Netflix just about a month ago, right in the middle of winter (for most of us, anyway.) While we were all comfortably snuggled in our onesies sipping teas, the director served us a visual feast - a most poetically beautiful lunch on a lazy summer day with a table of family members that are just all too similar to our own. It was Naples in all its glory, the sun, the intimate dynamics, the imperfectly beautiful romanticism; the city was the cast member of the film that needed no directing.

In this issue of Cartolina, Jacqueline Greaves rekindles the spirit of that beautiful scene because traditional Italian luncheons will always be in our hearts and our editor-in-chief Elisa Carassai brings back Issue 00’s food column Cibo Letterario featuring a special collaboration with Masterchedo aka Edoardo Notizia on a Neapolitan recipe.

It was the hand of God that brought this table together

By Jacqueline Greaves

It's not every day that you host a party for an acclaimed international director and his beautiful film – the case of Paolo Sorrentino and The Hand of God (È stata la mano di Dio.) This season, though gloomy, is always the most exciting time for the film industry globally as everyone anxiously awaits the Oscar nominations list, and for me, there is nothing more exciting than the Best Film and International Film categories. Paolo had already won a statue for The Great Beauty (La grande bellezza) in 2014, and that year, we also organized a dinner party of Academy voters in our home for this dear friend.

This time, however, we had an extra guest: the Covid virus.

Lists made, a menu created with possible allergies in mind, likes and dislikes, guest list, number of waitstaff, table presentation, floral decorations, candles, number of plates and glasses, and … what to wear. Guests were required to take a Covid test and therefore had to stop in the lobby. A first, and I'm sure the entire building was abuzz with whispers of the Monda activities this time. So glad to be cooking and not dealing with that new aspect of party planning. A nurse was at hand to test anyone who hadn't been pre-tested. It was almost entertainment by itself - the waiting with bated breath for results while masked between bites of appetizers and sips of wine.

Cooking for a Sorrentino party, considering that his incredible wife Daniela D'Antonio comes from Neapolitan restaurant royalty, some Italian meets Jamaican wizardry is necessary. Flavors must abound, and so out came dishes that included mushroom and pesto crostini, Jamaican beef pastries, pasta with a tuna sauce that sang of glorious southern Italian flavors, Jamaican Ackee & Saltfish, eggplant fritters, fried plantains, rosemary-sage-ginger veal meatballs, ginger-nutmeg gelato, citrus flan, Italian wine by Famiglia Cotarella and Jamaican Sorrel hibiscus-citrus-spice flavored punch. Because you absolutely have to refute what Paolo Sorrentino told Town & Country, "Big family luncheons are a custom that belongs to the past."

Jacqueline lives in New York City, where she has created, together with her husband Antonio Monda, a literary salon in which conversation and food nourish body and soul in festive harmony. The soiree, hosted by Jacqueline in collaboration with Netflix, had a guest list that included, among others, Sorrentino, Filippo Scotti, Daria D'Antonio, Robert De Niro, Jake Gyllenhaal, Isabella Rossellini, Francesco Clemente, and Joel Coen.

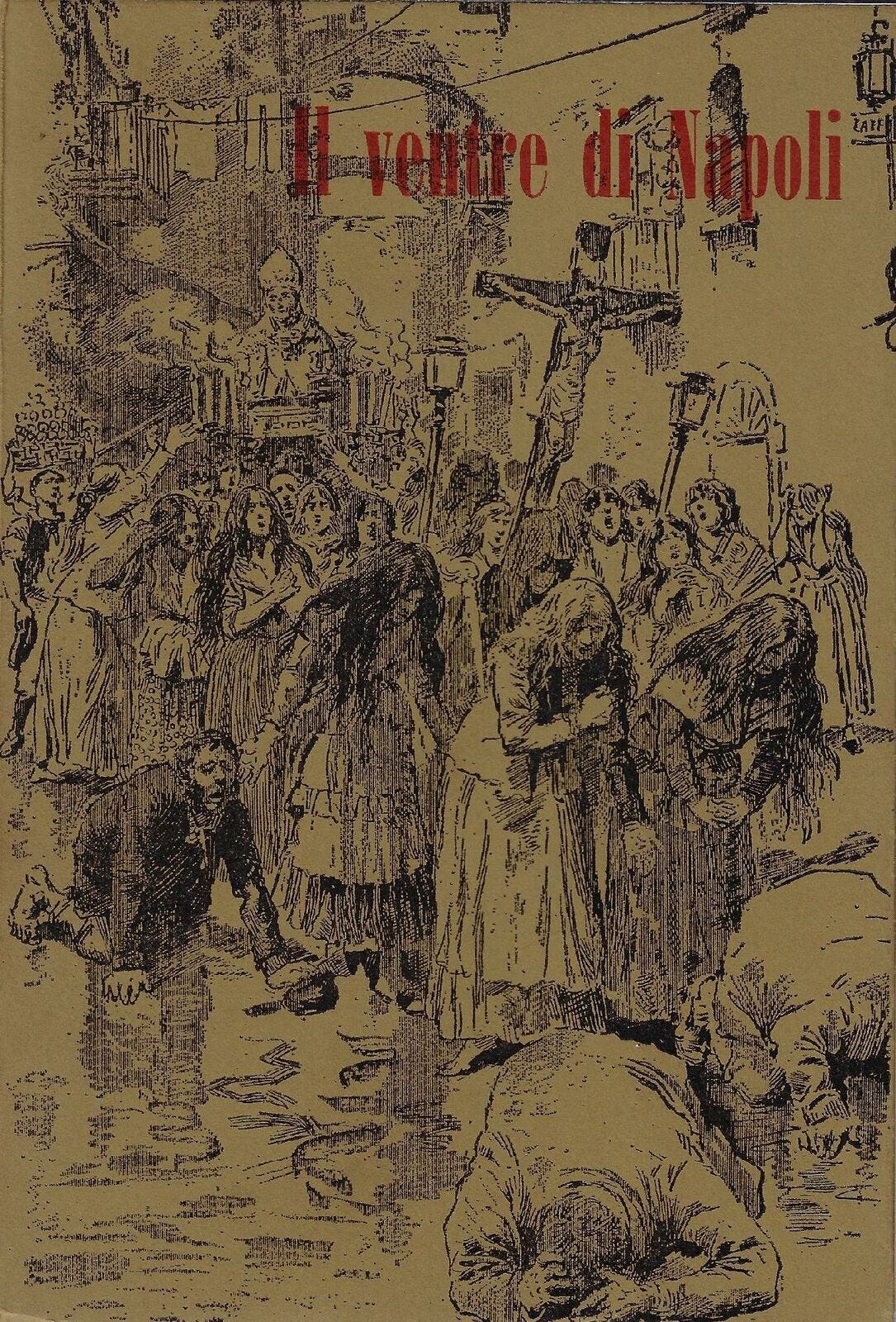

Cibo Letterario: Il Ventre di Napoli

by Elisa Carassai

Since we're feeling slightly sentimental this beginning of the year, we're back with the infamous column that debuted in our issue 00, Cibo Letterario. This time though, it will only be available for our newsletter subscribers. So while the first-ever Cibo Letterario column featured Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa's The Leopard, this time we recommence with a lesser-known but not any less important book, which I believe, was able to capture and document both the dark and good side of Naples' history: Matilde Serao's Il Ventre di Napoli.

The book takes up similar themes to "Le Ventre de Paris", written a few years earlier by Emile Zola. Through a series of almost-anthropological observations, it describes and analyzes the daily life of Neapolitans, taking as a pretext the proposal of the then Minister Depretis to reclaim the city, gutting precisely the poorest neighborhoods. With her novel, the writer immerses herself as much in the splendors as in the miseries of her beloved city, where the destruction cannot but generate pity and anger. Moved by indignation, the same that veins her sumptuous pen, Serao begins her work by launching an appeal to the government that, far from just any rhetoric, reveals the status of emergency that Naples was in at that time. Despite this, the journalist is moved when describing the hopeful attitudes of the Neapolitans who never disdained, living their days with beauty and magnanimity. The happiness of Naples is authentic since it is derived from every moment. And Serao is able to aptly capture this through her descriptions of what Neapolitans eat in the chapter dedicated to food, called Quello che Mangiano.

Below, you will find a translated excerpt from the chapter that inspired a reinterpretation of Napoli's famous Maccheroni by Edoardo Notizia, fondly known as Masterchedo.

“As soon as they have two pennies, the Neapolitan people buy a plate of cooked and seasoned macaroni; all the streets of the four working-class neighborhoods have one of those innkeepers who set up in the open air their cauldrons, where the macaroni always boils, the pans where the tomato sauce boils, the mountains of grated cheese, a spicy cheese that comes from Cotrone.

In fact, all of this apparatus is very picturesque, and painters have painted it, and it has been rendered by them neat and almost elegant, with the innkeeper who looks like a little shepherd boy from Watteau; and in the collection of Neapolitan photographs that the English buy, next to the nun of the house, the little thief of handkerchiefs, the family of lousy people, there is also the maccaronaro's Bacchus. These macaroni are sold in saucers of two money and three money; and the Neapolitan people call them briefly, from their price: nu doie, nu tre. The portion is small and the buyer argues with the innkeeper, because he wants a little more sauce, a little more cheese and a little more macaroni.

With two pennies he buys a piece of octopus boiled in sea water, seasoned with strong bell pepper: this trade is done by the women, in the street, with a little hearth and a small piñata; with two pennies of maruzze, you have snails, broth and even a cookie soaked in broth; For two pennies the landlord, from a large frying pan where they fry confusedly scraps of pork fat and pieces of offal, onions and fragments of cuttlefish, extracts a large spoonful of this mixture and places it on the bread of the buyer, taking care that the hot and brown grease does not drip on the ground, that it goes all over the crumb, because the buyer cares. As soon as he has three money, four money, eight money a day to have lunch, the good Neapolitan people, who are corroded by family nostalgia, no longer go to the innkeeper to buy cooked edibles, they have lunch at home, on the floor, on the threshold of the basement, or on a worn-out chair.

With four pennies he makes himself a large salad of greenish raw tomatoes and onions; or a salad of cooked potatoes and beets; or a salad of broccoli turnips or a salad of fresh citrioli. The wealthy people, those who can afford eight pennies a day, eat large plates of green soup, endive, cabbage leaves, chicory or all these herbs together, the so-called mmenesta maretata; or a soup, when the time comes, of yellow squash with lots of pepper; or a soup of green beans, seasoned with tomatoes; or a soup of potatoes cooked in tomatoes.

But most of the time he buys a roll of macaroni, a blackish pasta, of all sizes and all sizes, which is the rubbish, the confused waste of all the cartons of pasta and which is effectively called "monnezzaglia" (garbage): and he dresses it with tomatoes and cheese.”

Mezzanielli Lardiati (“A’ Lardiata”) by Edoardo ‘Masterchedo’ Notizia

Lardiata, in Neapolitan "a' lardiata", is a typical Neapolitan peasant cuisine dish that today still satisfies the refined palates of Neapolitans.

It appears that the origin of Mezzanelli Lardiati dates back to the 1700s, at a time when the noble Bourbons enjoyed rich dishes such as Timballo, Sartù di Riso, and Ragù alla Genovese, while the common Neapolitans consoled themselves with this delicious pasta course.

In Naples after World War I, extra virgin olive oil was considered a scarce and valuable commodity; hence the alternative was lard - 100% pork fat! Lardo di Colonnata (lard from Colonnata), the protagonist of this dish, is a cured meat native to the province of Massa Carrara with IGP (Protected Geographical Indication) certification, produced by curing the pig's fat in Carrara marble basins.

What you’ll need to serve 2:

50 gr of lard from Colonnata

200 gr of ziti spezzati or maccheroni lisci (pasta types)

A clove of garlic

250 gr of Piennolo vesuviano or San Marzano tomatoes

Sale and extra virgin olive oil to taste

1 chili

50 gr of aged pecorino cheese

A handful of fresh basil

How To:

Begin by finely mincing the lard until it becomes creamy. Heat pan with two tablespoons of extra virgin olive oil and sautee the lard with garlic clove. And then add the chilli.

Once the lard has dissolved, add the tomatoes (which can be substituted with peeled tomatoes) and cook over low heat for 15 minutes adding salt to taste. Set water to boil and once it is ready, add a few ladles to the sauce.

Add a dash of coarse salt to the pasta and drop them into the boiling water. Drain and continue cooking the pasta in the pan. The sauce helps retain the starch of the pasta for a creamier finish. Finish cooking by adding a ladleful of boiling water to the pan.

When the pasta is ready, turn off the heat and let it rest for 15 to 20 seconds in the pan. Add a generous grate of pecorino cheese, allow all the ingredients to come together, and serve with a drizzle of raw extra virgin olive oil and fresh basil leaves.

Name of Stamp: Napoli Italian National Championship 86-87

Year: 1987

We commemorate this edition of Cartolina with a stamp dedicated to the Napoli football club who won its first-ever national championships on the 10th of May in 1987. The team's road to success with the arrival of football legend Diego Armando Maradona sets the ambience in which Paolo Sorrentino recounts his childhood in his latest movie, The Hand of God.

Our magazine are available in select stockists all around the world and on our website. We want to hear from you! Talk to us by replying to this mail, or leave us comments below or via our social media channels. If you send us a postcard, we’ll stick it up on our office walls.

Until the next dispatch,

Elisa, Debrina and the rest of the Sali e Tabacchi Journal team.